These reflections on some of the Stations of the Cross are by priests of Old St Paul’s.

First Station: Jesus Before Pilate

PILATE

Cool water over my fingers flowing.

The upstart

Had ruined a night and a morning for me.

I thrust that stone face from my door.

I was told later he measured his length

Between the cupid and the rose bush.

The gardener told me that later, laughing.

And that a woman hung about him like a fountain.

Another woman stood between him and the sun,

A tree, sifting light and shadow across his face.

Outside the tavern

It was down with him once more, knees and elbows,

Four holes in the dust.

More women then, a gale of them,

His face like a scald

And they moving about him, a tumult of shadows and breezes.

He hung close to the curve of the world.

The king had gone out in a purple coat.

Now the king

Wore only rags of flesh about the bone.

(I examined cornstalks in the store at Joppa

And discovered a black kernel.

Of the seven vats shipped from Rhodes

Two had leaked in the hold,

One fell from the sling and was broken.)

And tell this Arimathean

He can do what he likes with the less-than-shadow.

No more today. That business is over. Pass the seal.

George Mackay Brown, from his Stations of the Cross

Pilate’s callous dismissal of Jesus and his casual mockery of his sufferings comes from a place of expedience and business-like ruthlessness. The body of Jesus, so pitifully evoked here – ‘four holes in the ground’, ‘rags of flesh about the bone’ – is, by contrast, guarded and shielded by the women, treasured. Pilate is more concerned about his precious grain consignment than this broken body. Before Pilate, Jesus seems utterly defenceless. And yet, ‘He hung close to the curve of the world’. For me, this depicts not only his falls under the weight of the cross but his choice to remain close to the earth, close to the poorest and weakest, close to those regarded as dispensable or acceptable collateral damage. It is, I think, not by accident that the characteristically laconic GMB hints at resurrection by mentioning grain. Jesus is the grain of seed that falls into the ground, the ground he abides close to, and dies so that it may bear much fruit. Against such fragility, the ‘seal’ Pilate affixes to the tomb will prove insubstantial, less than a shadow. What abides is this risen, broken body.

Station 2: Jesus Takes up the Cross

‘Lord, it is time. Take our yoke

And sunwards turn.’

George Mackay Brown’s sequence, Stations of the Cross, begins with fourteen beautifully concise mini-poems, one for each station. For this one, he manages to hint at several scriptural allusions in two short sentences. ‘It is time’ evokes St John’s ‘the hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified’ (Jn 12.23), a turning point in the narrative that points to the cross and leads immediately into his words about the grain of wheat falling into the ground. This long reflection then concludes in chapter 17 with Jesus’ prayer, ‘Father, the hour has come; glorify thy Son’ (Jn 17.1) and, ultimately, with ‘It is finished’ (Jn 19.30). This is not chronological time but the consummation of all time in the One who makes all things new.

‘Taking the yoke’ evokes a different scriptural tradition. Matthew 11.29 speaks of a light burden, an easy yoke. Surely the cross is no light burden! And it is light for us only because it has been borne by another. Nevertheless, El Greco’s painting of Jesus bearing the cross does have light about it, albeit light from a stormy sky. His face is not contorted with pain but at peace, trusting, tender. The cross is not merely carried but embraced, as if it were something to give life, as if it were a tree planted in the primordial garden, as if it were a sign of hope.

‘And sunwards turn.’ Face the rising sun. Face the dawn. Face Jerusalem’s empty tomb and find warmth, light and hope.

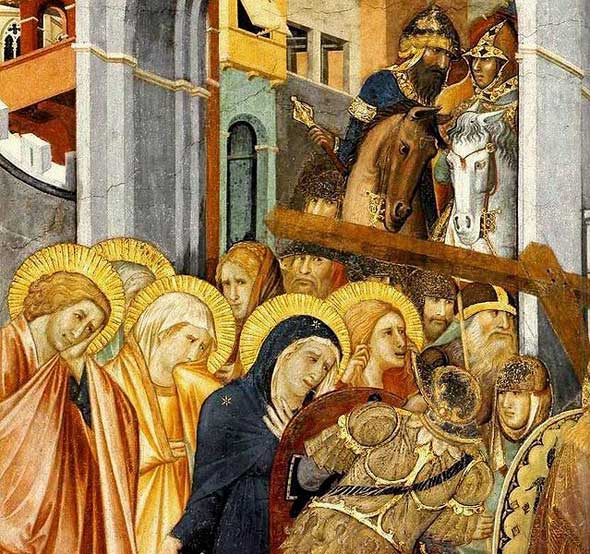

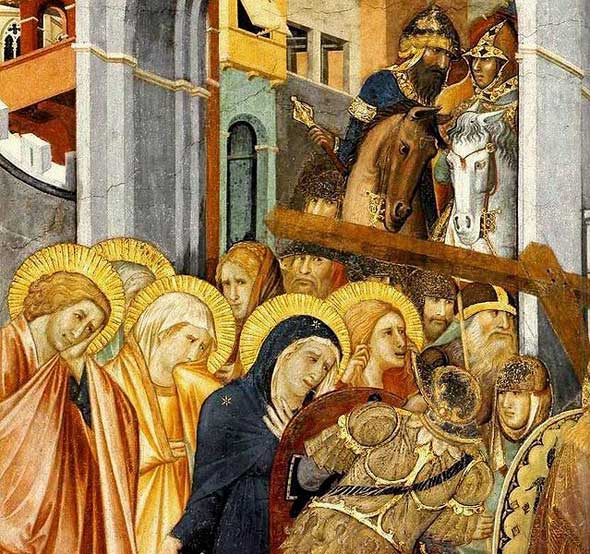

Station 3: Jesus falls for the first time

Raphael’s painting of c.1514-16 both depicts the current scene of the sequence – the first fall of Jesus – and sets up the next two by including both Mary and Simon of Cyrene. In the far distance are crosses already erected with crowds surrounding one – this is no exceptional moment for the ruthless machine of imperial control but just one more example to be made to hammer home the supremacy of might. Spears, armour, horses, banners, batons; military strength is arrayed above Jesus as if to show just how much he is subjected to it. But Simon stands strong and faces it down, suggesting that it is not absolute, for beneath the cross he shows to us that there is another story. Here, by contrast, is tenderness, love, devotion and pain. Here is the face of Christ which shows, in the face of brute force, only mercy, only pity. ‘Those who live by the sword die by the sword’. ‘But I say to you, love your enemies.’ And Mary’s face shows the same pained tenderness:

Illos tuos misericordes oculos ad nos converte

Turn those merciful eyes towards us.

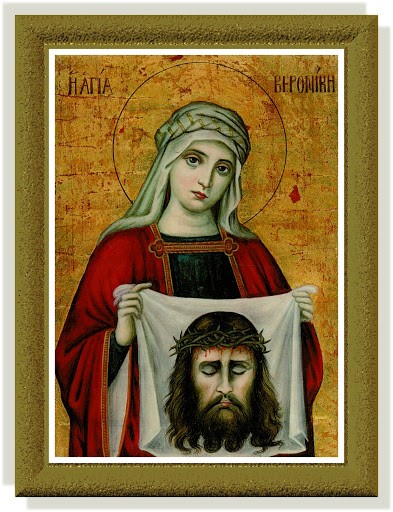

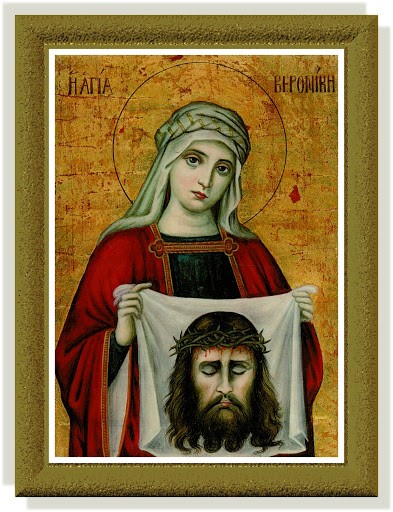

Station 6: The face of Jesus is wiped by Veronica

Who walked between the violet and the violet

Who walked between

The various ranks of varied green

Going in white and blue, in Mary’s colour,

Talking of trivial things

In ignorance and knowledge of eternal dolour

Who moved among the others as they walked,

Who then made strong the fountains and made fresh the springs

Made cool the dry rock and made firm the sand

In blue of larkspur, blue of Mary’s colour,

Sovegna vos

Here are the years that walk between, bearing

Away the fiddles and the flutes, restoring

One who moves in the time between sleep and waking, wearing

White light folded, sheathing about her, folded.

The new years walk, restoring

Through a bright cloud of tears, the years, restoring

With a new verse the ancient rhyme. Redeem

The time. Redeem

The unread vision in the higher dream

While jewelled unicorns draw by the gilded hearse.

The silent sister veiled in white and blue

Between the yews, behind the garden god,

Whose flute is breathless, bent her head and signed but spoke

no word

But the fountain sprang up and the bird sang down

Redeem the time, redeem the dream

The token of the word unheard, unspoken

Till the wind shake a thousand whispers from the yew

And after this our exile

T. S. Eliot ‘Ash Wednesday’

An anonymous woman is watching as Jesus is led out to the place of crucifixion and, moved by this young man burdened by the instrument of his execution, pushes her way through the gawping crowd, and taking out a cloth, possibly the head scarf she was wearing, wipes the sweat from his face. Why does she do this? Is this a statement? Does she recognise the Son of God? Is she simply protesting against the barbarity of this penalty? Or is this the response of a human heart to the suffering of another? Whatever her motive her act of compassion has earned her a place in the history of our redemption. She is an example to us how we are to respond to suffering wherever we find it. “In that you did it to the least of these you did it to me’” says Jesus and here we see this acted out on the way of the Cross. We can see the actions of Veronica all around us in the response to COVID-19, in the heroic act of our front line workers in the NHS, support services, and in the kindness of strangers in making deliveries and telephone calls.

Fr Paul Burrows

Station 8: Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem Luke 23.27 – 31

Here, in the longest utterance by Jesus in any of the gospel accounts of his passion, he addresses a group of women among the crowd following him.

Who are these women of Jerusalem? Given the many women disciples Luke features in his version of the Jesus story, it’s highly likely they are among his followers, perhaps quite recent ones. The response of Jesus to them could seem unnecessarily harsh. But that is perhaps to misunderstand Luke’s point here; in line with his focus on Jesus’ prophetic ministry, Jesus is responding to their pain and sorrow with words of prophetic warning. Thus the focus shifts from Jesus, and what is about to befall him, to events lying in the future, to the Jewish/Roman wars and the destruction of the temple and city of Jerusalem.

Where does this take us? I cannot help thinking of the increasingly urgent warnings about climate change and its likely impact on all of us, especially on poorer countries around the world – and of the apparent ignoring of those warnings by so many. But in this present time of pandemic, Jesus’ words also bring sharply to mind how unprepared our developed societies have been for something that many scientists in the field of virology have been warning about for some years.

Jesus’ prophetic words, like the Hebrew prophets of old, were meant to call the people to ‘repentance’, that is ‘to return to the ways of justice and compassion’. So, as we offer prayer for all who are suffering from the virus, let us also pray that leaders and people of every nation will work for the common good and for all that builds human community.

Lord Jesus, the women of Jerusalem wept for you: move us to tears at the plight of the broken in our world, especially all those currently suffering with the coronavirus. Teach us the ways of justice and compassion, and give us a heart to love our neighbour at this time, whether near or far away. Amen.

Fr Tony Bryer

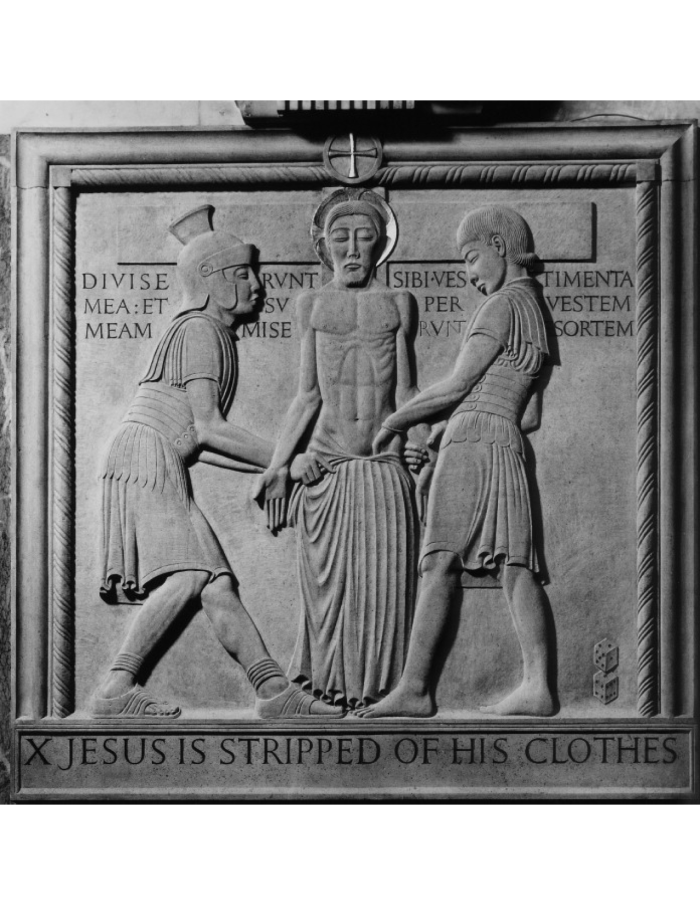

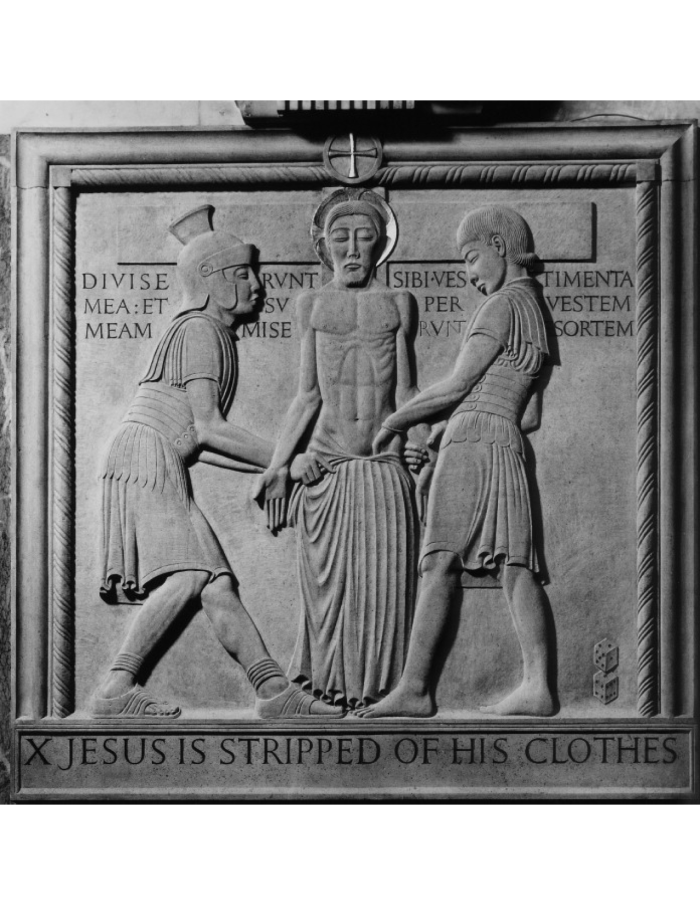

Station 10: Jesus is stripped of his clothes

At least since the stories of Genesis, nakedness has been a symbol of shame and humiliation. Tormenters know that, and history is replete with ritual humiliations or degradations involving forcibly stripping clothes from captives. Enslaved people were stripped and displayed as merchandise in both antiquity and in more recent times. Concentration camps developed elaborate systems of stripping people that combined terrifying demonstrations of power and the dispassionate redistribution of seized possessions.

And so it is at this Station of the Cross: Jesus is violated by stripping his garments in actions meant to dehumanize him, to terrorize him, and to provide an economic prize for his captors.

An extraordinary depiction of this is found in Eric Gill’s 1914 carving for Westminster Cathedral, where the sculptor captures the leering privilege of mercenaries given complete control of a prisoner. The violation they intend is menacingly ambiguous, while their anticipated reward is foretold in their chiseled hands and eyes, as well as in the waiting dice. The inscription behind them connects this violation with prophecy. This station is about the apparent triumph of power intent on objectifying and commodifying the Human One.

It didn’t succeed; even such absolute, humiliating, violating power succeeded only in dehumanizing itself, and a portent of Jesus’ exquisite endurance and eventual triumph can be seen in Gill’s portrayal of Jesus’ face. Eyes closed in defiance, Jesus embodies the truth that nothing is so powerful that it can separate us from the dignity born with each of us.

Forces of power may try to strip us of our dignity or even our humanity, but it cannot succeed: our identity was forged in the love of God, and nothing can separate us from that love, or from the One who made us in the Divine image.

For I am persuaded,

that neither death,

nor life, nor angels,

nor principalities,

nor powers, nor things

present, nor things to come,

Nor height, nor depth,

nor any other creature,

shall be able to separate us

from the love of God,

which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.

(Romans 8:38-39, Authorised Version)

Fr Michael Barlowe

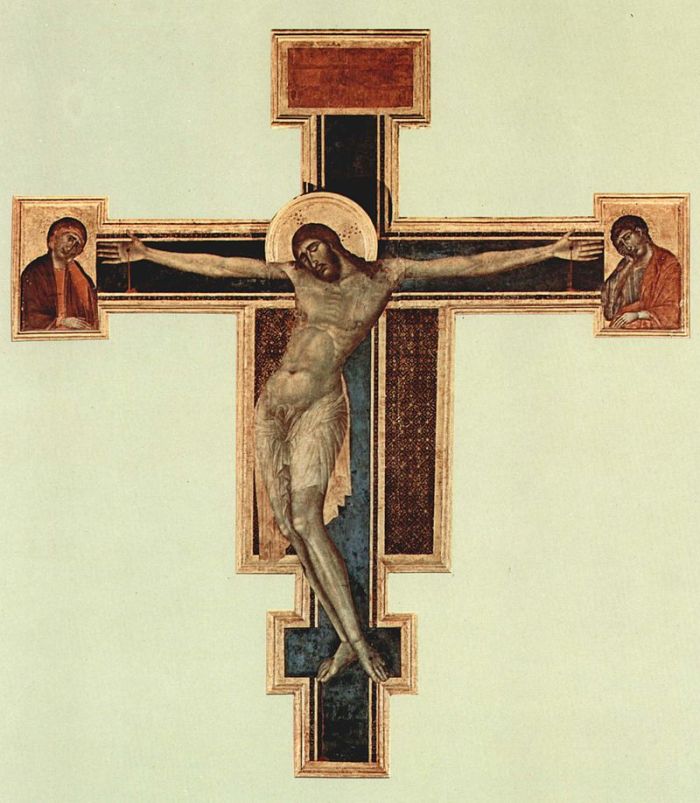

Station 12: Jesus Dies upon the Cross

The Killing

That was the day they killed the Son of God

On a squat hill-top by Jerusalem.

Zion was bare, her children from their maze

Sucked by the dream of curiosity

Clean through the gates. The very halt and blind

Had somehow got themselves up to the hill.

After the ceremonial preparation,

The scourging, nailing, nailing against the wood,

Erection of the main-trees with their burden,

While from the hill rose an orchestral wailing,

They were there at last, high up in the soft spring day.

We watched the writhings, heard the moanings, saw

The three heads turning on their separate axles

Like broken wheels left spinning. Round his head

Was loosely bound a crown of plaited thorn

That hurt at random, stinging temple and brow

As the pain swung into its envious circle.

In front the wreath was gathered in a knot

That as he gazed looked like the last stump left

Of a death-wounded deer’s great antlers. Some

Who came to stare grew silent as they looked,

Indignant or sorry. But the hardened old

And the hard-hearted young, although at odds

From the first morning, cursed him with one curse,

Having prayed for a Rabbi or an armed Messiah

And found the Son of God. What use to them

Was a God or a Son of God? Of what avail

For purposes such as theirs? Beside the cross-foot,

Alone, four women stood and did not move

All day. The sun revolved, the shadows wheeled,

The evening fell. His head lay on his breast,

But in his breast they watched his heart move on

By itself alone, accomplishing its journey.

Their taunts grew louder, sharpened by the knowledge

That he was walking in the park of death,

Far from their rage. Yet all grew stale at last,

Spite, curiosity, envy, hate itself.

They waited only for death and death was slow

And came so quietly they scarce could mark it.

They were angry then with death and death’s deceit.

I was a stranger, could not read these people

Or this outlandish deity. Did a God

Indeed in dying cross my life that day

By chance, he on his road and I on mine?

Edwin Muir

Fr Malcolm Richardson