Love of wisdom means always to be watchfully attentive in small, even the smallest actions. Such a person gains the treasure of great peace; he is unsleeping so that nothing adverse may befall him, and cuts off its causes beforehand; he suffers a little in small things, thus averting great suffering.

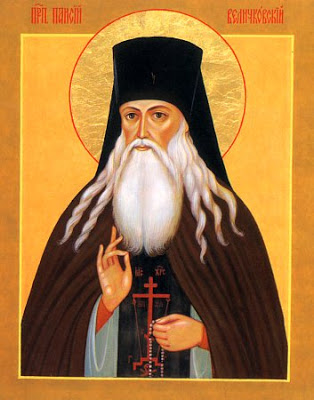

These words, quoted from St Isaac, are in the edited Russian version of the Philokalia, the Dobrotolubiye. It was compiled in the 18th century by St Paissy Velichkovsky and translated into Russian by St Theophan the Recluse in the 19th. These words occur in a section of the ‘Directions to Hesychasts’ by the monks Callistus and Ignatius, from 14th century Constantinople, just after the Hesychast cause was so powerfully championed by St Gregory Palamas. I give these bits of background simply to make the point that this rich tradition of spirituality has a long pedigree, even if it was little known in the West until the 20th century. Indeed, the English translation from which I’ve quoted by Kadloubovsky and Palmer from 1951 did much to bring this fine tradition to the attention of the English speaking world. But to the substance!

Hesychasm, of course, means stillness and stillness means an inner as well as an outer disposition. Attentiveness, watchfulness, wakefulness, sobriety are all synonyms for what we now know as ‘mindfulness’ and it’s important for Christians to know that we have our own deep sources for this practice. The acquisition of inner peace is a wonderful thing in itself and needs no justification, but it is also both a sign of the indwelling Spirit of God and a preparation for a fuller apprehension of divine beauty: ‘What is more joyful than the thought of the splendour of God?’ ask Callistus and Ignatius.

Attention to small things allows for a fuller awareness of the arising of thoughts in our minds so that they may be ‘cut off’ as they arise. This is core teaching in the desert tradition of Christian monasticism and has very close similarities with some Buddhist teachings. These ‘thoughts’ – logismoi – are the first stirrings that lead to anger, anxiety, distraction or greed, all the poisons that threaten our inner peace. That inner peace does not need to be created – it is our natural state – but it can easily be disturbed by these thoughts when they spiral out of control. But how do we first spot their arising and how do we then cut them off?

The practice of giving our full attention to small things is cultivated through patient effort in concentrating on the thing we are doing and by setting aside times of quiet prayer or meditation where we focus on a single point – usually a word or short phrase and/or our breathing. In hesychast prayer, this is not simply a mind-body exercise (though it is also that) but a loving attention towards the God who is the source of all life. In this way, our attention is not on our own immediate concerns but on that which is ultimate, and yet is also more intimate than we could imagine. This cultivation of attentiveness allows us to be more alert to the arising thoughts. Cutting them off simply means refusing to entertain them or allow them to develop. It may also mean replacing those thoughts with an appropriate word or phrase to counter its intent – ‘peace’, ‘love’, ‘mercy’. Evagrius of Pontus developed a whole range of such counter-words in his Antirrhetikos. But the main tool in this practice is ‘attention’ itself, something like a spiritual muscle that we can train through repeated and simple actions. For many, the constant repetition of the Jesus Prayer is the greatest tool we have in this journey towards a restoration of the inner peace that is our divinely created nature.