At a time when there are increasing pressures on priests and ministers to be professional, with those who have no experience in the ‘real world’ being particularly suspected of having nothing of any use to offer, I would like to make an appeal to the urgent necessity of clerical uselessness!

- The priest has nothing to offer. He or she is only there to serve as a symbol of what is of absolute value.

- The priest has nothing to give. Each of us has all that we need to become the fully free human being we are invited to be. But it does help to have someone to remind us of this from time to time.

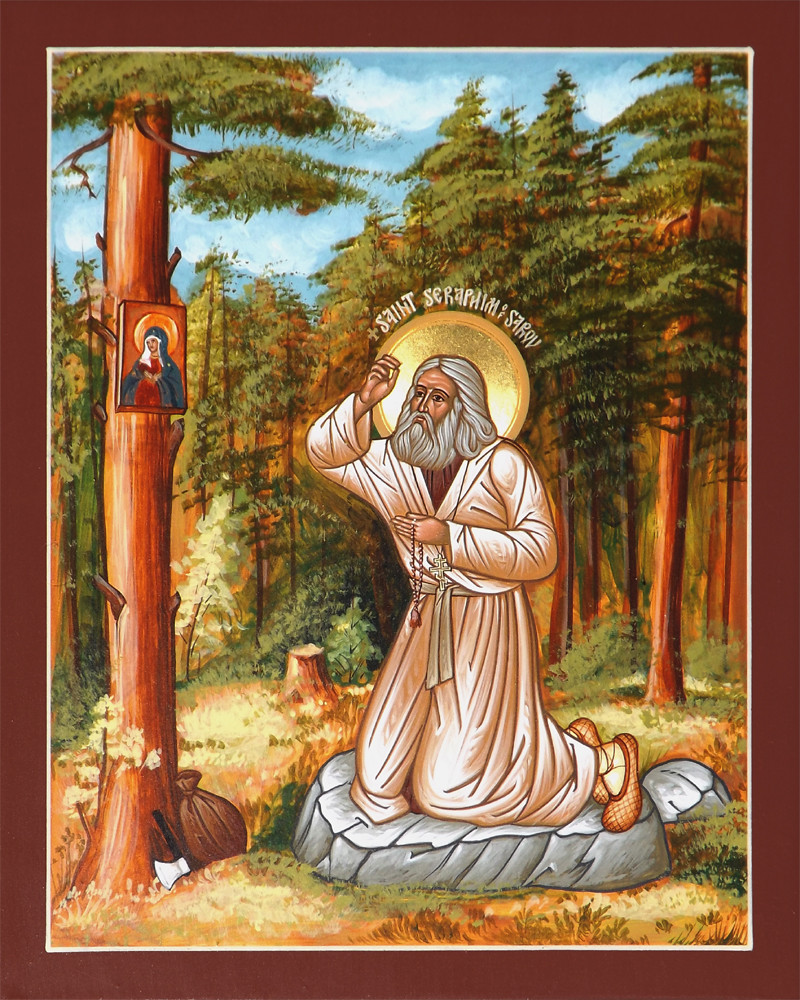

- The priest is primarily engaged in useless ‘activity’. Prayer, the primary business of priests (which isn’t to say that it’s not everyone else’s primary business), has no value in the world – it has no goal, no measure, no purpose and no standard. It accomplishes nothing more than is accomplished by a bird of the air or a flower of the field.

- The priest has no specialism, no professional accreditation. All that matters is that she or he is conscious of standing in a lineage of those who commit themselves to way of being. As Zen teaching would say, it’s a matter of mind-to-mind transmission, not special learning.

- The priest is incompetent. In matters of spirituality, who is competent? All that matters is that the priest has an awareness of a Great Doubt – a fundamental sense of our deepest longing – and a Great Faith – a fundamental sense that this longing can be directed towards something fulfilling.

- The priest has no work plan other than to be present.

- The only work a priest claims to do is absurd, because it claims to be the ‘work of God’.

The strange thing is, I think the church needs this particular brand of uselessness. And I dare to suggest that those not in the church are crying out for it too. Well, that’s enough for now. I’m off to sit in silence on a cushion for half an hour. What insanity!